Keen-eyed visitors to downtown Navasota may notice a colorful logo included on a sign mounted onto the wall of Dr. Donna Canney’s building at the intersection of the town’s two main thoroughfares: Washington Avenue and La Salle Street.

“Train Town USA,” the sign proclaims, juxtaposing images of classic steam and diesel locomotives on either side of the Union Pacific Railroad logo. In 2012, when the company celebrated its 150th anniversary, it began the “Train-Town” program, and Navasota was one of the first locales in Texas to be so honored.

“The railroad is the main reason Navasota is here,” town mayor Bert Miller told the Houston Chronicle newspaper in a 2012 article entitled, “Navasota: The Town That Trains Built.” Miller is still mayor of the Grimes County community, and the trains still keep passing through his town, as many as 30 times a day.

Adjacent to the Union Pacific tracks which bisect Navasota’s Historic Downtown District listed on the National Register of Public Places, is the old cotton gin that is the current Navasota residence of Bryan real estate developer Zane Anderson. In restoring the 10th Street building, Anderson refreshed the sign that was painted along the side of the structure facing the railroad tracks.

Once again, the sign proudly proclaims: “NAVASOTA COTTON.”

Just five years after Navasota was founded in 1854, the Houston and Central Texas Railway extended a line of track into the fledgling town. An offer was first made to build the line through nearby Washington, the birthplace of Texas, but leaders there declined the opportunity. Soon, Navasota became a bustling boomtown, loading raw–and eventually processed–cotton and its byproducts onto train after train after train. From that point, Washington, despite its historic importance, never stood a chance of competing with its nearby municipal rival.

As for the “chicken-and-egg” element of this story, cotton came to the Navasota area long before the train. Cotton was introduced to Texas by Spanish missionaries and then embraced by white settlers who, over time, took up the plantation-style business model of the Deep South. Thus with a perceived need to preserve the slave labor force which drove cotton production on Texas plantations, the Lone Star State rebelled against “Northern aggression" and fought on the side of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

After the war, the influx of vanquished Confederate soldiers searching to resurrect their old agrarian ways in Central Texas, coupled with the presence of newly-liberated slaves freed from the area’s existing plantations, triggered an outbreak of violence and lawlessness from which Navasota increasingly suffered for the next several decades.

Railroad Street became the hub of much of the town’s infamy and vice.

Today, Railroad Street is the site of public and private redevelopment efforts looking to restore a block-long stretch of historic buildings in the downtown area. Zane Anderson is redeveloping the south end of the block, while in the middle, Houston attorney Steve Scheve and his wife Janice are in the midst of an ambitious four-year restoration of the P.A. Smith Hotel, once known as the “jewel of Navasota.”

Train Town USA is again a city on the rise, and when the Smith Hotel reopens its doors–the Scheve’s are hoping for a late-summer launch–the trains of Navasota will be there right outside the main entrance to both welcome and bedazzle onlookers, albeit in a more tranquil and refined setting than the rip-roaring times for which the town became so well known more than a a hundred years ago.

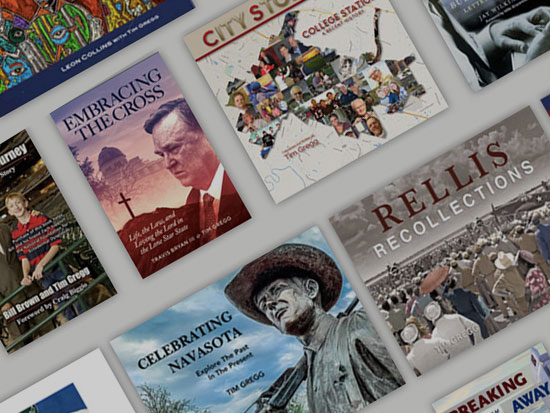

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE© 2025 Tim Gregg. All Rights Reserved.