For many years, I considered my life’s single most significant turning point to have taken place at a pay phone outside the washrooms of a basement bar inside the Empire State Building. It was October 1986, and I had just turned 30 years of age. My “dream job” had just been offered to me, and I called my parents to give them the good news.

“I going to work in tennis!” I exclaimed, hoping to be heard over the cacophony of New Yorker’s celebrating the end of another work week.

Less than an hour earlier, I had accepted a position as public relations director on the Virginia Slims World Championship Series. This was the tennis big time. I had played tennis in high school, but Richard Raskind’s experience notwithstanding, I never dreamed I’d have the chance to be a part of the women’s pro tour.

You may know Raskind by another name: Renee Richards. She would be one of a number of the sport’s notable figures with whom my path would cross.

On the phone with my mother that Friday night in midtown Manhattan, I was having difficulty getting her to understand just how much my life had suddenly changed.

“Thank goodness you’ve found a job,” she said.

Bessie Gregg–née Prochaska–grew up in Oklahoma the youngest of 13 children born to parents who had emigrated from what would eventually be known as Czechoslovakia, then later the Czech Republic, and now Czechia–“to make it easier for companies and sports teams to use the name on products and clothing,” according to the BBC. In the north-central environs of Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl and Great Depression years of the early 20th Century, Mom was often called a “Bohunk,” a term used contemptuously by mean-spirited locals to describe those of Eastern European descent. Think “spic” or “polack” to describe others from faraway lands.

Mom never took kindly to being perceived as a second-class citizen. With a dozen older siblings to protect her, she developed a quick-tempered defense mechanism to put people in their place, which she also employed occasionally in raising her only child.

Nuance, nor an appreciation for a bigger picture of life were never of much interest to my mother. Either I had a job or I didn’t. There was no gray area in between.

Some of her tempestuousness, as I would learn later in my engagements with tennis players from every corner of the globe, appeared to stem from her Czech DNA. Think Martina Navratilova and Hana Mandlikova.

That’s Hana in the photo above. More on her later.

“Mom, this isn’t just ‘a job,’ I told her on the phone. “It’s the chance of a lifetime.”

“I don’t know about that,” Mom replied, “but its time for you to get back to work. When do you start?

Before I could tell her, my father, on an extension in my parent’s home, broke in. “Tim, we’re really proud of you.”

“Thanks, Dad. I’m sort of proud of me, too.”

My parents were a classic example of opposites attracting. Wendell Gregg–who went by his middle name of Felix–met my mother at a small grocery store in the Oklahoma town of Enid, A single woman in her late 20’s, Mom worked there. A single man in his mid-20’s, Dad shopped there, more and more frequently as I was once told, because he developed a crush on Miss Prochaska. Sadly, I never bothered to learn the details of their courtship but they were married in 1950 and I came along in 1956, their one and only child.

Dad was the oldest of four children, raised on a farm just a few miles south of Enid. The youngest of that brood, my Aunt Mo–who ultimately became vice chairman of Keller Williams Realty–described her father as a “sharecropper,” renting the land on which he farmed. Mo’s “angle” there was to portray her meager beginnings.

By the way, “Mo,” is short for Imozelle. And, yes, she is a remarkable woman.

My grandmother, Audra Gregg, was a teacher, strongly opinionated and impacted by diabetes for most of the time I knew her. She instilled in her children an appreciation for knowledge, the arts, and the overall world in which they lived. While Mom was a scrapper with but an eighth-grade education, my dad was a sensitive and kind man who started but never finished college.

To my knowledge, Mom never left Oklahoma during her childhood. My father got a tour of Europe for his 20th birthday, thanks to Uncle Sam and America’s involvement in World War II.

Those conflicting world views–Mom’s narrow and short-sighted; Dad’s broad and open-minded–impacted their take on the news I delivered from New York Ciity. Our brief conversation caromed between Mom’s somewhat cynical backhanded compliments and Dad’s defensive volley’s attempting to bolster my esteem.

That “rally”—pardon the tennis puns—took a little bit of the joy from the moment for me.

But Mom was right about one thing: I was glad to have found a paying job.

Here’s how that came to be.

When the Virginia Slims of Oklahoma arrived at the Summerfield Racquet Club in Oklahoma City in early 1986, I was a respected and award-winning radio sportscaster at the market’s top country music station, KEBC, whose tagline was, “Keep Every Body Country.”

I had been hired the year before as the station expanded its premier news operation to include sports. Owner Ralph Tyler had launched his media empire by way of an outdoor sign company, and he saw sports as a great marketing tool for his radio station. “I won’t tell you what stories to cover,” Tyler told me after I was hired, “but I want you to be seen at every high school in the metropolitan area.”

I took those words as a challenge and, ultimately, was honored by the Oklahoma High School Coaches Association for my coverage and support of secondary school athletics. I also received numerous awards for excellence from the Oklahoma Associated Press Broadcasters Association.

I was good at my job, but the day after being recognized by the Coaches Association in the summer of ‘86 I was handed my pink slip.

The move did not come as a surprise, and wasn’t a reflection on my job performance. Tyler had sold the station and when the new owners stepped in, a significant downsizing took place. For a short time, all that remained of the once-mighty and always-respected news operation was reporter Dan Mahoney–now vice president of corporate communications for the NBA’s Oklahoma City Thunder–and myself. Dan’s current boss, Thunder owner Clay Bennett, once tried to hire me to work for him, and that’s a turning point I’ll get to a little later.

When the Virginia Slims Series arrived in Oklahoma City about six months before I lost my radio job at KEBC, the tournament marked a revival of sorts. An earlier version of the event, called the Virginia Slims of Oklahoma City, had come to town in 1971 and 1972, in the early days of women’s professional tennis.

hat circuit was born in 1970, thanks in large part to the disparity in prize money offered at the time to men and women players.

The idea for women players to break away from the sport’s traditional governing bodies was that of Gladys Heldman, the New York-based publisher of World Tennis magazine. Heldman’s daughter, Julie, was at the time a top-ranked pro, and one can imagine that her mother was not pleased that her daughter wasn’t being paid her due. Enlisting the support of a small cadre of players–a group which became known as the “Original Nine” and included Billie Jean King, Nancy Richey, Rosie Casals, and Julie Heldman–Gladys Heldman launched the first-ever women’s pro tour. When tobacco magnate and tennis enthusiast Joe Cullman stepped in to offer the financial backing of his Philip Morris Company, the Virginia Slims Circuit was born, named after the recently-launched Philip Morris cigarette brand targeting women smokers.

Sixteen years later when the Virginia Slims Series returned to Oklahoma, the furor over a tobacco company sponsoring the game of women’s tennis had significantly diminished. Samples of various Philip Morris products were distributed at Series events, including the tournament in Oklahoma City, but were met with little fanfare or protest. Outside the tournament sites, lovely young ladies dressed in tennis attire handed out smokes. Inside the Summerfield Racquet Club in Oklahoma City, the real tennis-playing professionals were all business.

And as a sports reporter with a fondness for tennis, I was smack dab in the middle of my element.

“Smack dab.” That may be a phrase unfamiliar to some of you. According to the website dictionary.com, smack dab means “directly,” or “squarely,” and was “first recorded in 1890–95; ‘smack (in the sense “directly, straight”)’ plus ‘dab (in the sense “a quick, light blow,” used adverbially)’.”

You’ll find these little hiccups to the narrative flow throughout this book. I hope they don’t become annoying. That’s just the way my mind works. I guess you could call me a “tangential thinker.” The website GoodTherapy calls that “tangentiality,” which is:

“…the tendency to speak about topics unrelated to the main topic of discussion. While most people engage in tangentiality from time to time, constant and extreme tangentiality may indicate an underlying mental health condition, particularly schizophrenia.”

So, as we move along, you’ll now have a means to directly gauge my mental well-being!

I discovered professional tennis not long after Heldman launched what came to be called the Virginia Slims Circuit through the pages of her World Tennis magazine. Having given up on a baseball career that was undoubtedly headed nowhere after Little Leagues, I began looking for a new sporting pursuit. What I saw within the pages of World Tennis caught my attention.

I was particularly enthralled by the exploits of Stan Smith who won the 1971 U.S. Open while an active member of the United States Army. Another American tennis great, Arthur Ashe, also played tennis nearly full time during his mandatory military service. Both players served as exemplary role models and recruiting ambassadors for the U.S. Armed Forces during the height of the increasingly unpopular Vietnam War.

By the time of my high school graduation in May 1974, that conflict had come to an end, and unlike my father and grandfather before him–as well as my wife who retired from the Army at the rank of colonel–I never “served”…

…until I stepped onto a tennis court for the first time.

Get it? “Served.” Each point in tennis begins with a “serve.”

Pun intended.

Reading about Stan Smith in World Tennis magazine inspired me to give tennis a try and it was on the public courts across the street from the Enid hospital where I was born in 1956–and where my father died 47 years later–that I taught myself the game.

I played tennis two years in high school, actually winning a match at the state tournament as a senior. During my freshman year of college at the University of Oklahoma, I avenged the subsequent round-of-sixteen defeat I suffered when a fraternity brother arranged for a rematch with his old Del City High School classmate that had vanquished me the spring before. In tennis, I had found a sport I could enjoy for a lifetime, not only as a player but also a fan, so when the pro tour came to Oklahoma City during my sportscasting days, I was ready to give it the coverage I felt it deserved.

For the better part of the week when the women of the Virginia Slims Series were in town–from February 24 through March 2, 1986–I camped out in the “press lounge” at Summerfield. Tennis stories dominated my sportscasts. Among my best features for the week was a piece I put together on one of the legendary male figures in the annals of the women’s game, the fashion designer, author, and former spy, Ted Tinling.

“Teddy” as he was known to his friends, made quite an impression on me. He was tall, lean, impeccably-attired, and shaved his head a decade before Michael Jordan made the look fashionable within the sporting community. And, also like Jordan would do later, Tinling sported a three-carat diamond stud earring.

Tinling was a regular within the pages of World Tennis, and when I saw him at Summerfield, in his role as a Philip Morris “ambassador for the women’s game,” I was eager to talk with him. He readily accepted my request for an interview and, as it turned out, my knowledge of his importance to the sport made quite an impression on him.

When I met him for our interview, I brought a copy of his book, Tinling: Sixty Years in Tennis, with me. I had bought the book when it was first published in 1983 and enjoyed it immensely. Of Tinling, Billie Jean King wrote, “Ted…has spent a lifetime setting the stage for tennis. His dresses have adorned stadium courts all over the world. Ted is, and has been, an integral part of the international scene for more than half a century. He can talk about it with such (humor) and insight that a conversation with him is a great experience.”

Based on my own experience, I wholeheartedly agree with King.

Once we began the interview, I could sense Ted was surprised by how much I knew about him. He told me he had never been to Oklahoma before and had expected to see cowboys on horseback while in the state. I told him that wasn’t an uncommon site on ranches, but not commonplace in the city. When we concluded our talk, I pulled his book out of my bag and asked him to sign it. He looked at me knowingly, realizing why my questions had been so well-informed. He graciously accommodated my request.

To Tim Gregg,

Very happy to count you among my friends.

Ted Tinling

Oklahoma City 1986

During the tournament, there was another male figure on hand representing Philip Morris's marketing interests. His name was Kevin Diamond and his title was “public relations director.” His job was to serve as the liaison between the tournament players and sponsors, fans, and media. I spent enough time with him while he was in Oklahoma City that I later told a videographer friend from a local television station, Robert Allen, who was also a tennis enthusiast, “Kevin Diamond may have the best job in the world.”

The Virginia Slims marketers in New York did an outstanding job positioning the Oklahoma City tournament as a promotional vehicle for the brand; not by peddling their tobacco product, but by infusing good will into their sponsorship of tennis and role in showcasing the sport and its players to a local audience. This was due, in large part, to the savvy nature of the local public-relations pro, Barbara Jackson, who was hired to coordinate local media activities for the week. While her knowledge of tennis was limited, she knew the quickest way to a sports reporter’s heart –at least the males of the species–was through the belly. The press food at the tournament was terrific, as was access to nearly every story line reporters could come up with, thanks to Diamond.

Absent from the proceedings, however, were the sport’s biggest names, players like Navratilova, Mandlikova, Chris Evert and Gabriella Sabatini. Given the newness of the tournament and the size of the Oklahoma City market, the event was categorized as “Tier 2” by the United States Tennis Association. Prize money totaled just $75,000 and that was not enough to attract top-rated talent. Still, the level of play was outstanding and the tournament featured a local girl making good on the court.

Lori McNeil played her collegiate tennis at Oklahoma State University. She reached the NCAA quarterfinals for the Cowgirls in 1983, and was an All-American in both singles and doubles while in college. McNeil grew up in Houston, a young Black girl inspired by her mother’s love for the game. Years before the Williams sisters burst onto and then dominated the tennis scene, McNeil and childhood friend Zina Garrison, caught the attention of the tennis community as juniors playing out of their hometown MacGregor Park, under the tutelage of the director of tennis there, John Wilkerson.

Although Wilkerson was Black, the MacGregor tennis program involved mostly white youths. His free juniors tennis program, however, made the sport accessible to young players from all walks of life. It was at MacGregor, located south of the downtown Houston area near the University of Houston campus, Wilkerson first started coaching McNeil and Garrison years before either was old enough to drive. He remained their coach throughout their professional careers. Under his guidance, McNeil garnered a best-of-her-career world ranking of number nine in 1988. Garrison achieved a number-four world ranking in 1989.

McNeil reached the finals of the 1986 Virginia Slims of Oklahoma where she lost to Dutch player Marcella Mesker, who also claimed the tournament’s doubles crown. Mesker’s Oklahoma City win was the only singles title of her ten-year professional career. Her doubles win at Summerfield with Frenchwoman Pascale Paradis marked Mesker’s sixth and final pairs championship on the pro tour.

All in all, it was a great week for both Mesker and me, maybe the most fun of my ten-year-long sportscasting career. Afterwards, Jackson asked me if I would have any interest helping her at the upcoming Virginia Slims of Tulsa tournament that September. “And I can pay you,” she said with a laugh. “That’s great!” I replied, referring more to the opportunity than the need for compensation. I readily accepted her offer and began making plans to take a week’s vacation to free my time for the event.

Instead of vacation pay, however, by the time August rolled around, KEBC had changed ownership and I was receiving unemployment checks for the first time in my life.

My search for another job in radio did not go well. Rather than seeing the situation as a chance to make a new start, I languished in an increasing state of depression. I was good at what I did, but sports jobs were highly competitive. I had also been lucky to have worked my way up from a student broadcaster to sports director at a major-market station. For six years in a row during that time, at three different stations including KEBC, I had been honored by the Oklahoma Associated Press Broadcasters with their “Sportscast of the Year” award.

I found some solace in my upcoming freelance assignment at the Virginia Slims tournament in Tulsa. I found it both interesting and ironic that the tournament began on the day after my 30th birthday.

“Is that so?” Barbara Jackson exclaimed upon receiving that news when I met her in Tulsa on the Sunday before the tournament started. “That’s great! Happy Birthday!”

“Thank you and glad to be here,” I replied.

I had shared with Barbara earlier that I was now looking for a new job. She had recently filled a full-time position on her staff, although at the time I had no interest in leaving broadcasting. “Something is bound to turn up,” she told me. I replied, “I hope so. I’ve never had to actually look for a job before.”

Turning our attention to the tournament, I asked Barbara if Kevin Diamond was working the event.

“No, he’s not here,” she said. “The Slims PR person here is a woman. Her name is Annalee Thurston.

“And by the way, we’re not supposed to call it ‘Slims.’ It’s ‘Virginia Slims,’ and the players aren’t ‘girls’ or even ‘ladies.’ They’re ‘women.’”

“I’ll remember that,” I said with a smile.

Although I did not know it at the time, both Kevin Diamond and Annalee Thurston had impressive tennis pedigrees. Diamond’s father, Jerry, had been director of the second-ever women’s pro tournament, and later became executive director of the Women’s International Tennis Association. Thurston’s time in tennis began in her job with Billie Jean and Larry King’s International Sports Marketing firm. Although King today is a seminal figure in the gay-rights movement, for many years she was married to husband, Larry, In fact, Larry King–not the famous television talk-show host—played a significant role in bringing Heldman and Culman to the table to start the women’s pro tour. Shortly after the Virginia Slims Circuit was born, Larry King hired Thurston to assist in promoting their tournaments.

In meeting Thurston in Tulsa, I found her to be a charming, no-nonsense kind of person. She possessed a cool and confident air, a California girl with a winning smile, blonde hair, and smoldering brown eyes. I never asked–because gentlemen don’t–but I guessed she was a few years older than me. When we first met, we talked surprisingly little about the upcoming tournament. Instead, she seemed amused by my ceaseless questions about what it was like to work in tennis.

“How long have you been associated with the sport?” I asked.

“Since about the time Virginia Slims started sponsoring women’s tennis,” she said. “I came on after graduating from Cal State-Long Beach with a degree in business administration.

That was in 1971. I graduated from the University of Oklahoma in 1978. In describing her time with International Sports Marketing, she told me about working the famed “Battle of the Sexes” match between Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs played in Houston on September 20, 1973.

I had watched that match on television and rejoiced when King dispatched the 55-year-old Riggs, a former player on the men’s tour, in straight sets. I wasn’t ever a fan of “male chauvinist pigs.”

The Virginia Slims of Tulsa was played at the city’s Shadow Mountain Racquet Club, an outdoor venue. In reviewing the tournament draw sheet with Thurston the Sunday evening before the event’s week-long run, I saw many the names of many of the players who had competed in Oklahoma City. As the tournament unfolded, several of the players remembered me from Oklahoma City. A few were surprised that I was now working the event. Annalee noticed my easy camaraderie with the players and pulled me aside at the end of the first afternoon session.

“You seem to know some of these players better than I do,” she laughed. “I don’t often work Tier 2 tournaments, but Kevin wasn’t available this week so I had to step in. I’ve got a lot of other things I need to be working on, so I was hoping that you might be willing to handle my on-court duties and the post-match player interview requests for the rest of the week.”

I was pretty sure I could do what I had seen Kevin Diamond do in Oklahoma City.

“Since a lot of the players here are not well known,” Thurston reminded me, “you probably won’t have all that much to do, but don’t run off!”

I got the sense that Thurston saw Tulsa as “beneath her pay grade.” She had been hired into her present position by Philip Morris in 1984, and thanks to her long association with the Kings, was well-known and well-regarded in the game.

“I got this,” I assured her. “You can count on me.”

“Good,” she said, obviously relieved to be relieved of her tournament-site workload. “If you need anything just call me at the hotel. That’s where I’ll be the rest of the week.”

And she wasn’t kidding. I didn’t see her again until the weekend of the semifinals and final rounds of play.

Barbara was delighted when I gave her the news of my increased responsibilities. “Better you than me,” she said. “I knew there was a reason I wanted to have you here this week.”

The rest of the tournament—at least from my perspective—went without a hitch. As a broadcaster, I’d spent the better part of ten years around athletes so this wasn’t new territory for me. Since none of the top players were there, I didn’t run into any unruly egos. The local media was interested in getting to know the players who were there and I stayed busy shuttling them to and from the press room. Sunday’s final again featured Lori McNeil, this time pitted against Beth Herr, a former University of Southern California standout. Herr had beaten McNeil on her way to winning the 1983 NCAA championship three years before.

When Thurston came into an empty press room the morning before the finals, she spotted me sitting in a corner reading the Tulsa World newspaper’s coverage of the event.

“Good morning,” she said. “Glad you’re here. I have something I want to talk to you about.”

I put the paper down and pulled up a chair so she could join me.

“It’s been a good week,” she said. “and I’ve been hearing a lot of good things about you.”

“Well, I’ve had a lot of fun,” I replied. “There’s a reason these women play at the top level. I’m impressed.”

“And it seems they’re impressed with you, too. How would you like to do this full time?”

I sat in silence processing her words. Before I could respond, she continued.

“Kevin’s wife is not happy he’s away from home so much. I think he’s going to be moved into auto racing. Philip Morris sponsors an Indy Car team under the Marlboro brand and he’ll do great there. We’re going to need to find his replacement. I think you might be a great candidate for that job.”

I was stunned, but quickly responded. “I think so, too.”

“I’ve told the staff back in New York about you. I think they’re interested. Oh, and Ted has spoken very highly of you as well.”

“Ted Tinling?” I asked.

“From what I hear, you and Ted really hit it off in Oklahoma City. He thinks you would be a great choice for the job.”

We sat looking at each other with silly grins on our faces. I was happy I had made a good impression with so many people.

Thurston said she would relay my interest in the position to the powers that be. I had learned in Tulsa that she and Diamond both held the titles of “public relations director” for Virginia Slims tennis. Technically, Philip Morris was merely the title-sponsor of the women’s professional tour. The circuit was administered by the Women’s International Tennis Association, but the two entities worked hand in hand for the good of the game.

McNeil beat Herr in the Tulsa finals, 6-0, 6-1. Thus, it was my privilege to escort the former Oklahoma Sate Cowgirl into the interview room for her post-match press conference with the local media.

Both Lori and I were very happy with our results in Tulsa. It was Sunday, September 28, 1986. I was giddy as I began the two-hour drive back to Oklahoma City, but by the time I arrived home, my inherently pessimistic nature had taken root. Thus, as the ensuing days rolled by and no calls came about the job, I fell into a significant funk.

I’m a little ashamed to admit–both to you the reader as well as to myself–that I’m the kind of person (was then and remain so today) who lapses into a “ye, of little faith” mindset.

That term also aptly describes my take on religion in the early years of my adulthood, so pardon me for taking a tangential aside.

I grew up a Catholic, but was married–the first time–in the Lutheran Church because my future wife was of the faith. I thought a spiritual change of scenery might snap me out of my increasing indifference toward organized religion, but such was not the case. After we got married and settled in for our final semester of college, my wife and I sort of gave up on the going-to-church-on-Sunday thing. I was still a believer in God the Creator, but had grown apathetic about the act of weekly worship, and my wife followed my lead.

Fortunately, I got my spiritual act together.

For several years during my broadcasting career and after my first marriage ended, I dated a woman named Patty. When she moved to take a new job in another city, we embarked on a long-distance relationship. Then, when I got a new job much closer to her–she lived in a north-side Oklahoma City suburb while I took the job of sports director in Norman, where I had gone to college on the south side of the metro area–we rejoiced. But while my move seemed like a good thing for us, over time, we began to struggle and our issues ultimately put our relationship in jeopardy.

I went to bed one night–alone after another argument with Patty–and in an intensely vivid dream, a battle was waged for my soul. The dream made clear that Jesus Christ was on my side against a nemesis who bore the look and demeanor of Satan. As I slept, Christ entered the arena against evil on my behalf and emerged victorious. When I woke up the next morning, I was “saved.” When I called Patty and told her of my experience, she was ecstatic and I felt ”different,” but in a good way.

In the next few weeks, I shared my coming to Jesus story with several Christian friends, and without exception, their reactions were the same. Each person felt inspired to give me advice on how to be a stronger Christian. A common thread running through their instruction boiled down to what singer Bobby McFerrin would famously proclaim two years later: “Don’t Worry. Be Happy.” To do that, my Christian friends told me, I simply needed to give my concerns and worry to God.

For someone like me, though, that was easier “sung” than done.

A week after my return from the Virginia Slims of Tulsa tournament, and with little to do to distract me from my consternation, I had become an emotional wreck. Over the course of just seven days, my optimism had given way to despair. Hope became fleeting, thanks to the increasing–yet unfounded–negativity that filled my thoughts.

“You’ll never get the job.”

“Why would they hire you?”

“You should have known this was too good to be true.”

“Just crawl back into bed and feel sorry for yourself.”

Yeah, that was me, home alone in my one-bedroom apartment feeling increasingly sorry for myself. Even doing simple chores became an ordeal.

So, I saw as a positive thing, my effort late on a Monday morning to walk into my kitchen, open the cabinet door below the sink, and pull out the grocery sack stowed there to collect trash. It was stuffed to the point of overflowing, so I picked it up, turned, and headed out the front door, down the stairs, and out to the dumpster next to the tennis court adjacent to my building. After reaching my destination, just as I was about to give my garbage the heave-ho, a thought crossed my mind.

“Why don’t you let go of this worry and give it to God?”

Without missing a beat as the trash went flying, dumpster bound, I mused to myself, “Might as well give it a try.”

I stood there for a moment reflecting. I was tired of feeling miserable. Over the preceding weekend, when I’d done little but scavenged leftovers from the refrigerator, I’d begin asking myself, “What is wrong with me?”

“Give it to God,” I pondered. I wasn’t sure how that was done, but as I headed back to my apartment, I realized I felt better. Was this relief? Had my “load” been “lifted”” As I began climbing back up the stairs to my apartment, I felt a new sensation.

Peace?

Maybe.

If I was writing a script here instead of a book, if my life story was to be told in movie form, this scene of me turning from the dumpster and heading back to my apartment would be a crane shot from above, the camera lens pulling out to suggest my world expanding in that moment. Cut then to a medium shot from ground level of me, with a small smile on my face, walking past the camera’s point of view and out of frame to begin heading up the stairs.

And then with my character out of frame, a phone would begin to ring in the background, because in real life, that’s exactly what happened. Heading up the stairs to the front door I had left open, the phone inside my apartment was ringing.

Dashing into my kitchen, I picked up the corded handset of my wall phone and answered, “Hello.”

“Tim?”

“Yes.”

“Hi, this is Nancy Byrne with Virginia Slims tennis…”

New York was calling. FINALLY!

With a pleasant and cheerful manner, Byrne apologized that she had not been able to get back with me the week before.

“Are you still interested in the public-relations director position?” she asked.

“Yes, ma’am” I told her, unsure of her age–she sounded young (and turned out to be the daughter of former New Jersey Governor Brendan Byrne)–and wanting to be as respectful and endearing as possible.

“Good! We’re ready to meet with you. Could you come to New York this Friday?”

For someone who had spent more than two years plumbing the depths of the Oklahoma City-area high school sports scene by car, those were words I wasn’t accustomed to hearing.

“You want me to fly?” As soon as I said that I felt like a hayseed.

“Uh, yes,” she said. “We’ll buy the ticket once you tell us which flights work best for you.”

“Friday works fine for me,” I replied. “I’ll move some things around on my calendar.”

I chuckled to myself. There was nothing to move.

Okay, in the big scheme of things pertaining to my faith and grace and commitment to the Lord, THAT phone call might have been a bigger turning point than the one with my parents from the Empire State Building.

The “give it to God thing” had worked like a charm. And as I reflect on my life in the pages to come, God is going to enter the picture at just the right time a lot.

The “right” time being His time.

Byrne booked me a flight to the Big Apple on Thursday of that week. When she asked when I’d like to return home, I told her I’d never been to New York, so getting to spend a Friday night there would be a real treat.

“No problem,” she said. “You’ll love it here.”

The week’s worth of wait and worry had tempered my optimism for actually landing this job. And, rather than giving THAT to God, too, I started trying to make a compromise with HIm, which went something like this:

“Hey, I’m getting an all-expenses paid trip to New York, and that ain’t a bad way to spend a couple of days when you’ve got a little time on your hands. And if nothing else, I’ll go see ‘Cats!’ That’s a heckuva deal on its own. Hey, God, I don’t really NEED to get this job!”

Of course, I was trying to kid myself. You never kid God.

Upon arrival Thursday afternoon, October 8, my first taste of New York City left me a little nonplussed. I flew into LaGuardia Airport, which, at the time, was more than a little dank and dingy and in dire need of at least a fresh coat of paint. It truly paled in comparison with the Will Rogers World Airport in Oklahoma City from where I had departed that morning. Not only was Will Rogers newer and shinier with broader concourses and brighter seating areas, but also (in a bit of tangentiality here) it was the only airport in the world named for someone who had died in a plane crash. At least that’s what I thought I knew at the time.

Oh, how wrong. MANY airports, as it not-so-unexpectedly turns out, are named for victims of aviation disasters.

Chicago’s O’Hare Airport was renamed in honor of Navy aviator and Medal of Honor recipient Edward “Butch” O’Hare after he died in a plane crash in the Pacific Ocean during World War II.

In fact, the three largest airports in the Oklahoma City area are ALL named for people who perished while flying. Wiley Post Airport is named for the first person to circumnavigate the world alone, AND the individual who piloted the aircraft in which he AND Will Rogers lost their lives near Point Barrow, Alaska, in 1935. Tinker Air Force Base, located in the Oklahoma City suburb of Midwest City, is fittingly named for the first Native American to reach the rank of Major General, Clarence Tinker. And yes, Tinker died while leading an aerial combat mission against the Japanese near the Pacific island of Midway in 1942.

Many other U.S. Air Force installations bear the name of aviators killed in the line of duty.

Having survived my flight to New York, I hailed a cab to take me to the Grand Hyatt Hotel on East 42nd St. Leaving the airport, I could already see ahead in the distance the world-famous New York City skyline. Most recognizable were the towering Empire State Building in Midtown and the unmistakable gleaming facade of the United Nations Secretariat building along the west bank of the East River.

Arriving at my destination, I was dazzled by the sights that greeted me both outside the hotel’s revolving front doors and inside its two-floored reception area. “So this is what they mean by ‘hustle and bustle’,” I thought to myself. On the street, the sidewalks were packed with pedestrians. Inside, the line at the registration desk was long with travelers checking in for their stay.

After reaching my room, my first order of business was to check the room-service menu for a late lunch. I was astounded that a hamburger cost $12 (in 1986 currency), but my room was comped by Philip Morris and I ordered away with glee.

Next, I thumbed through the oversized New York City phone directory for the number to the Winter Garden Theater box office. That’s where “Cats” had begun its historic Broadway run on October 7, 1982. Almost four years to the day later, I hoped to be able to savor the acclaimed theatrical experience. When I reached the box office and asked about tickets for “tonight’s show,” I was informed that only a few remained and all were singles.

“That’s me!” I told the woman on the other end of the line. “I’m single and need only one ticket!”

“Our best available seat in the house is $45. Would you like that?”

I wouldn’t be able to expense the ticket, but for my first Broadway show I would spare no expense.

“First time in New York,” I proudly announced. “I’ll take it!”

Next, I called Nancy Byrne to let her know I had reached the city. She confirmed our meeting time the next day at 10 a.m. and asked if I needed anything, perhaps a restaurant recommendation for dinner. “Nope,” I told her. “I’m going to see Cats tonight.”

“Really?” She seemed impressed. “You got tickets?”

“Just one,” I said. “Going alone.”

The ticket stub which I have saved from that show–along with the complimentary Playbill magazine, souvenir program, poster, and sweatshirt–indicates I was seated on Row N. Entering the theater, I encountered a completely unexpected sight: that of an open stage already set in full back-alley glory. No curtain would rise to start this show. In fact, “Cats” was a fully immersive experience with cast bounding throughout the theater. At intermission, attendees were welcomed to come onto the stage and meet a few of the performers. Surprisingly, there wasn’t a rush for that experience. Most of the theater-goers retreated to the lobby for refreshment and relief. I simply remained in my seat, mesmerized by the experience.

“Cats” was spectacular in the “Now-and-Forever” manner promised by the tagline on the show’s promotional poster. My trip was already a success, yet the fun was only beginning. The next day held yet another dream-come-true adventure to which my interview would be but a postscript: a run through Central Park.

I had taken up jogging four or five years before as a result of an innocent-but-scathing comment by the young son of a friend of mine. That friend was John Phillips, boys basketball coach at Sooner High School in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, later to become the head men’s coach at the University of Tulsa. John’s son was named Duggan. He was four years old at the time I first met him, a cherubic-looking little lad. It was on a visit to John’s house to meet his wife, Leah, that little Duggan walked over to where I was sitting to let me know, “You sure do have fat cheeks.”

Out of the mouths of babes…

At the time, I was maybe 24, 25 years old. Covering other people playing sports for a living had taken a toll on my own level of fitness. Waking up at 4:30 each weekday morning and then covering sporting events, mostly high school games, at night, left me with little free time, and what free time I had mostly went to naps. Because I failed to make working out a priority, I had put on a few pounds. Working with Phillips Petroleum Company, my wife, exercised regularly at the employee fitness center. She never complained about my weight gain, but Duggan’s comment got my attention. The very next day when I got home for my mid-morning work break, I put on some gym shorts, laced up a pair of tennis shoes, and trotted off from the duplex where my wife and I lived, heading to a nearby entrance to Bartlesville’s Pathfinder Parkway to take up the sport of jogging.

I barely made it the two blocks to the parkway when I began to feel gassed. Not long afterward, I stopped. I checked my watch. i had “run” for exactly six minutes.

Eight weeks later, wearing a rather expensive pair of New Balance running, I was putting in 80 miles a week.

I kept up the obsession that running became through moves to Norman and Oklahoma City for radio jobs. I had backed off the mileage somewhat, but I was still an avid jogger and on my trip to New York, seeing “Cats” wasn’t the only thing on my Big Apple Bucket List.

A glorious autumn morning greeted me as I pushed through the revolving doors of the Grand Hyatt, still incredulous that I had seen “Cats!” the night before. I allotted plenty of time to get in my run and a cleanup before my interview at the Philip Morris building across the street from the hotel. I still remember vividly the first steps of that run. I can still see, hear, and smell the bumper-to-bumper traffic along 42nd Street. I had no choice but to stay on the sidewalks and dodge pedestrians on their way to work as I began my workout.

I quickly discovered that Grand Central Station–more accurately known as “Grand Central Terminal” and the hub of commuter rail traffic into and out of Manhattan–was next door to the Hyatt. Had I gone left instead of right, I would have instead run past the Chrysler Building which also was less than a block away.

As I made my way west of the hotel, I turned right onto Seventh Avenue and headed through Times Square to Broadway, which took me past the Winter Garden Theater and ultimately to Columbus Circle on the southwest corner of Central Park. From their, I meandered through the park, encountering fewer joggers than I expected. My hope was to emerge briefly from the park along Fifth Avenue to catch a view of architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece, the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum.

Central Park’s 86th Street Transverse took me to Fifth Avenue, where I turned left and in three blocks, there was the Guggenheim. The outside of the art gallery/museum looked almost otherworldly surrounded as it was by high-rise apartment buildings. Not until a few years later though, when I made a special trip back to New York to see Matthew Barney’s “Cremaster Cycle” exhibition at the museum, was I finally able to gaze in wonderment at the inside expanse of the Guggenheim’s rotunda and the architectural genius of Wright’s spiral-ramped interior design.

Crossing back into the park after passing the Guggenheim, I headed north along East Drive to the 97th Street Traverse where I doubled back and headed south for my return to the hotel. Along the way on Fifth Avenue, I passed the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the building housing the Frick Collection, the FAO Schwartz toy store in its original Fifth Avenue location near Central Park South (now an Apple retail outlet), and then, between 51st and 50th Streets, the majestic St. Patrick’s Cathedral. There, I noticed people walking up the front steps and entering the church doors. Without giving the matter a second thought, I jogged across the street, up the stairs, and into the sanctuary for a dose of Morning Mass.

I found an empty pew in the back of the church and kneeled to give thanks for the bountiful blessings during my short time thus far in New York City. Although technically “born again” and still in search of a new permanent denomination with which to affiliate, given the environs of St. Patrick’s, it was easy to fall into my childhood cycle of short Catholic prayers. After finishing, I asked God to give me wisdom and clarity for my interview and help me to be “the best I can be.”

I left before Mass ended and had plenty of time to spare before my interview.

Nancy Byrne had asked to meet me in the lobby of the Phillip Morris building at 120 Park Avenue. Without giving her my physical description, she recognized me immediately as I walked in. “Annalee and Ted both told me to look for the bluest eyes imaginable,” Byrne said. I chuckled softly with the knowledge that my most striking feature was due in large part to the tint of the contact lenses I wore. Without them, or the pop-bottle-bottom thick glasses I also wore both then and now, the world is a blur to me at more than 20 feet.

But through my contacts as a young man of 30 in 1986, I saw fine, and Byrne and I headed up the elevator to the Marketing Promotions offices to see if I had what it took to work in tennis.

“I won’t be asked to hit any balls this morning, will I? My game’s a little rusty.”

Byrne laughed politely. “Do you play?” she asked.

“I did in high school and live next door to a court, but I don’t pick up a racket as often as I used to.”

“Maybe that will change,” she offered.

Yes, I thought. I’ll have a lot of free time if I don’t get this job.

During the interview, I dealt mostly with just two people.

The first was Diane Desfor, a former touring pro who had played college tennis at the University of Southern California. Just a year older than me, Desfor had graduated Phi Beta Kappa from USC with a degree in psychology. After her retirement as an active player, she attended law school, so her “bonafides” working with Philip Morris were impressive.

Desfor was friendly and easy to talk to. She laid out the specifics of the job. Technically, I would be a contractor to the company, not a full-time employee. “That means when you’re not on the job,” she told me, “you can do other things, if you’d like.” I couldn’t imagine what those other things might be. I knew how to be a sportscaster and since sports were most people’s hobbies or recreational pursuits, I was a bit adrift when it came to filling up free time. As Desfor outlined my compensation package, I learned I would make considerably more than what I had earned in radio.

“All your expenses on the road will be covered,” she added. “Plus the frequent-flyer miles you earn will be yours.”

Desfor concluded our conversation by sharing with me the timeline by which her group hoped to fill the position. “We still have a couple other people we want to talk to. After that, we hope to make a decision within the next couple weeks.”

“Sounds good,” I said. I looked forward to giving that wait to God and not spending all my time in a perpetual state of amxiety.

From Desfor’s office, she escorted me to a nearby conference room where I met the group director of Marketing Promotions, Ellen Merlo.

Truth be told, I had done little to prepare myself for this moment at hand. I probably could have reached out to either Diamond or Thurston for advice, but the thought to do that never occurred to me. Other than a few short prayers at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, I was simply relying on my past experiences and professional instincts.

At first glance, I could tell Merlo was all business, She was tall, with dark eyes and black hair and had an air of confidence that, no doubt, served her well in her rise up the corporate ladder. Her welcoming remarks, though, put me right at ease. She asked me to tell her about myself, and as I did, she began taking notes.

Miraculously, I had an answer for every question she asked. A good answer. On my flight back to Oklahoma City the next day, in reflecting on my time with Merlo, I realized that it had been, for lack of a better way to describe it, an “out-of-body” experience for me. Not once did I pause before answering one of her questions. Everything she wanted to know about me, my past, my present, and my thoughts on a prospective future in women’s tennis prompted a relaxed, easy, and compelling response.

After my interviews were finished and we all wished each other well, I headed back to the bank of elevators which had brought me to this place. As I waited for my car, I thought to myself, “Man, I knocked that out of the park.”

During my interview, a couple of personal matters came up. “You’re not married, right?” Desfor had asked. “I think you know that’s why we’re looking for Kevin Diamond’s replacement. Being on the road is tough on a marriage.” She then added, “Let alone being on the road with a large group of women.” She laughed but didn’t elaborate, nor did I ask her to do so.

Near the end of my conversation with Merlo, she also touched upon a matter of “decorum.”

“Rule number one in this job,” she said, “is that you can’t date players.”

“Sounds like a good policy,” I said, although a sudden thought leaped into my consciousness:

“Aren’t most of the players gay?”

Fortunately, those words never made it out of my mouth. I certainly did grasp how complicated a liaison with a player could make things for everyone involved. Later, though, I learned Philip Morris had a number of former players under contract to serve as “goodwill ambassadors” for the company, much in the manner of Ted Tinling—who was gay. Several of these former players, as it turned out, were also gay and actively dated current players.

Billie Jean King met her wife, Ilana Kloss, when Kloss was a top-ranked double player. Most of the players during my time on tour, I came to realize were straight, but it never mattered to me one way or the other. I idolized them all, and many of them became my friends.

Back in my hotel room after the interview, I felt the same glow as when Annalee had suggested I could find myself in the exact position I was now in: a candidate for a job in professional tennis. With the purpose for my trip behind me, I turned my attention to spending Friday night in the big city with “friends” who had invited me out for dinner.

Those friends, in reality, were barely acquaintances. I had met Margo when she was a member of Barbara Jackson’s PR staff. It was her departure that created the opportunity for me to help Jackson at the Virginia Slims of Tulsa event. Margo’s husband had taken a job in New York City. Jackson must have told her about my interview there and in a phone call before I left Oklahoma City, she invited me to have dinner with her and her husband.

We arranged for them to meet me at the hotel at 6 p.m.

Not completely sure where we would actually meet, as the appointed time neared I waited at the top of the escalator linking the ground floor to the hotel’s second-floor reception area. After seeing “Cats” and running through Central Park, I was beginning to feel like I might actually belong in a place like this. I had no expectation for when I might someday return, but when I did, I knew I would never be a stranger in the big city again.

Lost in these thoughts, I was surprised to see Desfor coming up the escalator. She spotted me about the time I saw her and when we made eye contact, her face broke into a wide smile. After reaching the second floor, she walked over to where I was standing.

“Tim, I’m so glad I caught you!” she said. “When Nancy told me you were spending another night here, I decided to come over and see if I could find you.”

I told her of my plans for the evening and expressed my appreciation again for her time with me that morning.

“I think I have some good news,” she then said. “We’ve all talked and we’d like to offer you the job.”

Tears well up in my eyes now as I write these words. “Hearing” them again in my recollection of the moment, never gets old.

I immediately said “yes,” then reached out to give her a hug. Diane told me we would talk on the phone early the next week and work out the details. My job would begin with the start of the indoor season early the next year.

“I guess you’ll have something to celebrate tonight,” Desfor said warmly.

“Indeed I will,” I replied and gave her another hug.

Desfor suggested I wait for Margo and her husband outside the hotel in case they had driven into town. It turned out they lived in Manhattan and had taken a taxi to the hotel. When I hopped in to joy them, settling into the back seat with Margo, I asked if there was a place to eat inside the Empire State Building. I figured it would be fitting to cap off this memorable day by acquainting myself with another New York City landmark.

And that’s how we wound up in the basement bar from which I called my parents. During that conversation, I realized I would finally be able to follow in the footsteps my father left on foreign soil in service to his country.

“It took a World War to give both you and Grandpa a chance to tour Europe,” I said. “I’ll be heading there, too, but there will be no gunfire. The only shots I’ll hear will be on a tennis court.”

That experience was everything you can imagine it might be.

Two moments stand out in my recollections of the Virginia Slims World Championship Series. Both involved the same player, who, unknowingly, helped give me a new perspective on the woman who had raised and done her best to nurture me.

My first stop on tour was an indoor event in Worcester, Massachusetts at the penultimate event of the 1986 circuit season. I was there simply to get a taste of what was to come.

After entering the indoor arena which doubled as at the basketball court on the Holy Cross University campus, I followed the “players only” signs into the bowels of the building, ultimately walking down a hallway that led out onto the court. As I reached the entrance–it was between matches–I suddenly heard my name being called from a fair distance away. At least I thought it was my name, with a thick coating of a familiar Eastern European accent.

“Teem? Teem?”

I turned to look and noticed a figure at the far end of the hall.

“Are you Teem?”

I walked toward the stranger and quickly realized it was a woman trying to confirm my identity. As she began walking toward me, I suddenly recognized her.

It was Hana Mandlikova, who at the U.S. Open in 1985 had beaten both Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova to win the tournament, the third of her four career Grand Slam singles titles.

How did Hana Mandlikova know who I was???

As we met, the Czech-born player wrapped me in her arms, then held me out at arm’s length to get a good look.

“It is so nice to meet you, Teem!,” she said. “I hear you are from Oklahoma City.” When I told her that was true, she went on. “My agent lives in Oklahoma City, so I am very glad to have you here with us. If there is anything I can do for you, just let me know.”

With little more left to say, Hana turned and made her way back toward the women’s locker room. She had a good tournament in Worcester that week. As the tournament’s number-two seed, Mandlikova lost to the top-seeded Navratilova in the all-Czech finals of the Virginia Slims of New England, 6-2, 6-2.

Our paths did not meaningfully cross again until almost a year later at an indoor tournament in Chicago.

Mandlikova had turned pro at the age of 16 and won her first Grand Slam singles title at the 1980 Australian Open just two years later. She captured her second Aussie title to start the 1987 season. Given that Australia is half a world away and, thus, the cost to get there is sizable, I was not sent to Melbourne to witness Mandlikova’s triumph. Instead, I made my tour debut at the Virginia Slims of Kansas in Wichita, a Tier 2 event.

It turned out, I was the “Tier 2 guy,” but that didn’t bother me in the least.

Mandlikova spent most of 1987 ranked fourth in the world, behind Steffi Graf, Navratilova, and Evert. At that year’s U.S. Open, seeded fourth, Mandlikova reached the fourth round, but rather than play on one of the stadium courts as was fitting her seed, she was relegated to an outer court to face a young up-and-coming German by the name of Clauda Kohde-Kilsch. Mandlikova had a meltdown on her way to defeat, losing 6-1 in the final set. She then took out her frustration by pounding the on-court scoreboard with her racket. She was fined for the outburst, and then fined again when she failed to make an appearance at her mandatory post-match press conference.

Her next tournament was nearly two months later in Zurich, Switzerland, where she reached the finals, losing to Graf. Her return to U.S. soil came in Chicago, a Tier 1 event. And as it happened, I would be there to serve as the media liaison.

Because Mandlikova had not spoken to the press following her U.S. Open loss to Kohde-Kilsch, Chicago marked the next opportunity American reporters had to talk with her about what had gone so horribly wrong at Flushing Meadow.

Hana breezed through her opening-round match in an afternoon session in Chicago, but not a single reporter was there to speak to her. The next night, hers would be the feature match of Round Two and plenty of reporters were on hand to cover the event. She would face Kate Gompert, a tour veteran, Stanford grad, and a truly nice person. Ranked just inside the world’s top twenty, Gompert was a steady baseline player who could be a real nuisance when she was having a good day.

That evening in Chicago, Gompert beat Mandlikova 6-2, 7-6.

Immediately after the match ended I headed onto the court to choreograph the post-match interviews. Meeting the media was a requirement for all players as the press promoted the sport and helped put money into the players’ pockets. Thus, refusal to talk, as Mandlikova had done after her U.S. Open defeat, resulted in a fairly stiff monetary fine.

Knowing how unhappy Hana would be with another unexpected setback to a lesser-ranked player, I approached Gompert and asked if she could do her interview first. This was a big win for Kate and she was delighted to oblige. Then, I stepped over to Mandlkiova, who was not in a happy place, and told her that Kate would meet the press first, so she could have some time before being interviewed.

“F—- you!” she snapped. Grabbing her racket bag and her towel, she stormed off the court well ahead of Gompert’s exit, a horribly unsportsmanlike gesture.

I stood there for a moment, agreeing with Hana. “I’m f—-ed,” I thought to myself.

As I brought Kate into the interview room, several reporters came up to me before the proceedings began. “We’re on deadline,” they said in unison. “We need to talk to Hana. Is she going to be here?” Getting her side of the story about her Open defeat, and now her loss in Chicago, would make for big news on the nation’s sports pages.

“That’s the plan.” I said, already fearing the worst.

Once I got Kate started with the press, I headed toward the woman’s locker room, hoping to curtail Mandlikova’s expected early escape and begging her to talk to the media. Even though it had been only a few minutes after the end of the match, I had no idea if she was even in the locker room, and, as a man, the women’s locker room was off-limits for me. Annalee could have entered and easily corralled Mandlikova, but as a man working in this world of women, I could not.

I waited. And waited. Finally Gompert returned from her press conference.

“Kate, could you tell me if Hana is still in there?” I asked. “Don’t say anything to her if she is, just let me know.” Gompert agreed, opened the locker room door, looked around, then looked back at me. “She is,” Gompert said, nodding her head.

“Good,” I replied. “Thanks.”

Sooner than I expected, Hana emerged, her eyes cast down. When she looked up, she saw me, and for a moment, I don’t think either one of us was sure of what would happen next. Then, Hana walked toward me, and in a manner which reminded me of our very first encounter the year before in Massachusetts, she reached out to give me another hug. “I”m sorry for what I said on court,” she offered. “Let’s go get this over with.”

As I watched Hana explain to the press corps how the pressures of the game sometimes got the best of her, I was reminded of two things. I had grown up with a mother of Czech descent with the same sometimes unpredictable and fiery nature as that of Mandlikova.

“Must truly be a Czech thing,” I thought, and after further contemplation realized it might be a part of my own genetic make up as well.

And then something else occurred to me. Hana’s apology was a reminder that God remained in control of both my daily life and long-term destiny. Just as He had blessed me with the long-awaited phone call from New York and all the right answers in my interview, that night in Chicago with Hana, I had been His vessel to provide a great and proud tennis champion some peace and tranquillity.

Two weeks before my trip to Worcester, a letter arrived for me in Oklahoma City, from none other than Ted Tinling.

10/23/86

Dear Tim:

I have been hearing favorable whisperings about you within the corridors of (S)lims tower for some time! Today, at last, I see your name listed along with my own on a staff sheet, so I presume it is at last safe fo me to tell you WELCOME ABOARD! This I do very sincerely remembering our pleasant associations in Oklahoma City. Please assure that I am always available should there be any time in which you think my advice could be helpful. Look forward to you being with us in the near future.

Sincerely,

T.T.

———-

In researching this account of one of the most important turning points of my life, I discovered a story that ran in the March 16, 2015, issue of the Palm Springs Desert Sun newspaper:

Tennis legends pay tribute to Annalee Thurston at awards reception

Annalee Thurston, pioneering sports executive, assistant to Billie Jean King and Indio Chamber of Commerce manager died in May, 2007 at the age of 55 after suffering a brain aneurism. The annual awards reception benefits a scholarship, given in her name, to a top female graduate of the University of Oregon to attend the Warsaw Sports Marketing Center in pursuit of a career in sports business and management

The award named for Annalee is now annually presented at a reception and dinner for The Love & Love Tennis Foundation of Coachella Valley, which, according to the Desert Sun was:

(e)stablished in 2015 by (Rosie) Casals and Tory Fretz. (T)he foundation’s mission is to promote, support and offer financial grants to youth tennis organizations, academies, foundations, schools or individuals who promote the growth of the sport. The foundation also assists in developing juniors who participate in tennis tournaments and aspire to become collegiate or professional tennis players

At the 2022 Love & Love dinner, Billie Jean King was honored with the Annalee Thurston award. King told the assembled gathering:

“The work the foundation does here is so needed and inspiring…making a huge difference in the lives of so many children, and they are doing it through tennis. I am honored to be recognized with this award because it is special, due to the fact it represents the best of women and their accomplishments. Annalee was a dear friend from my hometown of Long Beach. This award is a wonderful way to celebrate the legacy of someone who was loved by all.”

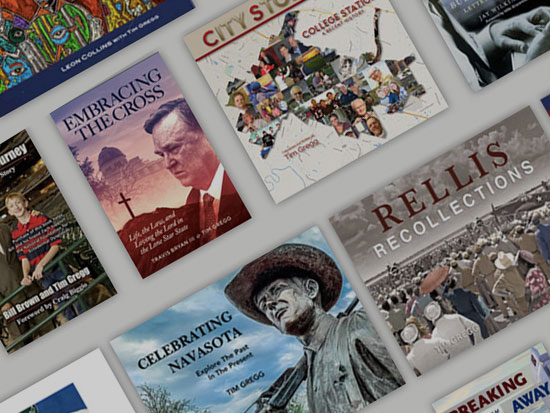

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE© 2025 Tim Gregg. All Rights Reserved.